In this interview, Dr. Kamran Aghayev, a neurosurgeon specializing in vascular compression syndromes, talks about the evolution of our understanding of Eagle Syndrome, its connection to jugular vein compression, and the surgical approaches that offer the best outcomes for patients.

The following is a transcript of the full interview. You can watch the video at the end of this article.

What Is Eagle Syndrome?

Bassam: Can you tell us about Eagle Syndrome? What is the background?

Dr. Aghayev:

It’s a very interesting disease. It’s not as rare as most people assumed. It started in the 1930s and 1940s when an ENT surgeon from the United States, Dr. Eagle, noticed something interesting. He saw some people after tonsillectomy getting pain in the throat and difficulties with swallowing. Sometimes those people would get pain in their head, face, and various symptoms in their neck, face, and head—mostly related to pain.

He noticed that most of these people felt like their pain started right after surgery and was somehow related to tonsillectomy. One thing he observed was that they had quite long bone protrusions called styloid processes.

For those unfamiliar, styloid processes are extensions coming out of the skull base from the temporal bone. They project down like stalactites in a cave and serve as an anchor for several muscles and ligaments. Normally, they’re about 2 to 3 centimeters, but in some people, they can be quite long.

Dr. Eagle made the correct connection that when styloid processes are too long, they cause problems. He was the first one to point to this, and that’s how the syndrome was named after him—so it has nothing to do with birds or eagles flying in the sky.

Later on, we figured out that Eagle Syndrome is much more complex and broader than initially thought. Now we talk about vascular Eagle Syndrome as a variant—when the carotid artery or the jugular vein, which are nearby the styloid process, may somehow get compressed, stretched, or kinked in the vicinity of the styloid process. Sometimes we see nerves in the area compromised, leading to neurological problems.

The term Eagle Syndrome has broadened, and the way I prefer to call it is Atlantostyloidal Compression Syndrome. As the disease research evolved, we figured out that one of the most important contributions comes not from the styloid process itself, but from C1, which is called the atlas (the first cervical vertebra). The term Atlantostyloidal Compression Syndrome is probably a better term than just Eagle Syndrome.

The Critical Role of the C1 Atlas

Bassam: So this disease isn’t just from the styloid process—it can also involve jugular vein compression from C1?

Dr. Aghayev:

That’s right. The atlas is the first cervical vertebra, right beneath the skull. It’s mobile in relation to the skull, and in some cases, the atlas shifts forward. This shift pushes all structures in front of it forward—and the closest structure to the atlas is the jugular vein.

The jugular vein runs between the atlas and the styloid process. When the atlas pushes forward, it bends and kinks the jugular vein, sometimes pressing it against the styloid process. So the styloid process is passively sitting there while the atlas is pushing the internal jugular vein forward.

This push may be constant or dynamic—when we turn our head right or left, the atlas changes position relative to the skull base and may push the jugular vein more or less with head motion.

Surgical Treatment: The Only Solution

Bassam: What is the method or surgery to treat this disease?

Dr. Aghayev:

The only solution for Eagle Syndrome, vascular Eagle Syndrome, or Atlantostyloidal Compression Syndrome is surgery. There is no conservative treatment.

Back in the 1930s and 1940s, Dr. Eagle advocated removal of the styloid process from the mouth, through the tonsil fossa. The doctor would go into the tonsil area, make an incision, find the tip of the styloid process, and remove it. That was the treatment for a long time.

Later, we figured out that the condition is much more complex and associated with compression of nearby vascular structures. We learned empirically that styloidectomy (removal of the styloid process) alone is not sufficient in most cases. When you do styloidectomy from the mouth, you only remove the tip—it’s an incomplete resection.

In the vast majority of cases, the cause of compression is not coming from the styloid process itself—it’s coming from the C1 atlas. To achieve successful decompression, you need to remove the part of the atlas that is pushing the jugular vein or other structures.

Why Remove Both the Styloid Process and C1?

Bassam: If you remove both, you don’t leave any chance for jugular vein compression?

Dr. Aghayev:

It’s not only my opinion—it’s what the scientific evidence shows. The styloid process may cause compression of the carotid artery, which is well documented and can lead to strokes or transient ischemic attacks (brief episodes of neurological dysfunction caused by temporary loss of blood supply to the brain). It can disturb blood flow to the brain.

Think about the styloid process as a wall. As C1 pushes the jugular vein, the vein gets narrow and kinked, and in the last stage, it’s pushed against the styloid process. If you resect both the styloid process and the C1 transverse process (the lateral projection of the vertebra), you will get the best results—no question about it.

You don’t leave any chances of recurrence. You don’t leave any source of potential compression there.

Why Neurosurgeons Should Be Involved

Bassam: Eagle Syndrome surgery is common in ENT departments. As a neurosurgeon, what made you interested in this disease?

Dr. Aghayev:

The reason Eagle Syndrome is in the realm of ENT surgeons is because Dr. Eagle was an ENT surgeon. Historically, he was first to report this disease and discussed it with his colleagues. The classical version of Eagle Syndrome has to do with neck issues—pain in the neck, difficulty swallowing, pain when swallowing. These conditions, called dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and odynophagia (painful swallowing), are well known in ENT.

But the most feared complication of Eagle Syndrome is vascular complications—when it interferes with the carotid artery and jugular vein, impairing blood inflow to and outflow from the brain. The brain is a rather important organ, so neurosurgeons and neurologists should get involved.

It’s absolutely necessary for neurosurgeons and neurologists to familiarize themselves with this disease because it primarily affects the brain—basically blood circulation, inflow or outflow. Another reason: the main culprit is C1, and the atlas is a specialty of spine surgeons, which is a subspecialty of neurosurgery.

Unfortunately, there aren’t too many neurosurgeons involved in the care of Eagle Syndrome. Most neurosurgeons don’t know this disease or haven’t even heard about it, which is unfortunate.

Addressing Concerns About Spinal Stability

Bassam: Does removing part of C1 affect neck movement or stability?

Dr. Aghayev:

Opinions are good, but to answer these concerns, you have to look at the data—the scientific evidence. People ask about C1-resection-induced instability because ENT surgeons they’ve met previously only talk about removing the styloid process without touching C1.

C1 is a ring-like structure, like a closed ring. The transverse processes—the part of C1 we’re removing—are small wings that protrude sideways from that main ring. It’s important to note that these transverse processes do not contribute to C1 stability. They work primarily as attachment points for some small muscles, which also attach to other bones.

There is no data indicating that removal of these transverse processes leads to any instability. This has been done for a long time in neurosurgery, and no such case exists where C1 transverse process resection led to instability.

When we do surgery for Chiari malformation (a condition where brain tissue extends into the spinal canal) or tumors inside the posterior fossa (the area at the back of the skull), we sometimes remove the part of C1 called the arc—and even that doesn’t lead to instability. From a stability standpoint, transverse processes are the least concerning. They can be safely resected. I’ve done many of these procedures and have never seen instability as a result of C1 shaving.

Why Stents Are Not an Effective Treatment

Bassam: We hear about stents as a treatment. What do you think about that?

Dr. Aghayev:

The jugular vein is being compressed between two rigid bone structures: C1 transverse process pushing forward, and the styloid process acting as a wall. Two bone structures are pushing the internal jugular vein externally.

A stent is basically a network of metallic wires in a collapsed state. You pass it through the narrow segment, then inflate a balloon to expand it. This works if there are no bones around—but the stent and balloon cannot push bone away. They don’t have that force. If they did, they would rupture the vessel wall.

So what happens? The parts of the stent that hit bone cannot expand, while the parts in soft tissue expand—but those areas aren’t compressed anyway. You’re hurting the part of the vein that isn’t damaged.

Another reason to avoid stent therapy: it ruins your surgery. If you push a stent inside the jugular vein and it doesn’t open, it stays there. With time, the stent becomes part of the wall. If you then do proper surgery and resect the styloid process and C1, the jugular vein cannot expand because it’s no longer elastic. You’ve ruined your chances of recovery with surgery.

Stents can work only if the styloid process has been removed, C1 has been removed, and there’s residual narrowing from soft tissue or a clot. In 99% of cases, if surgery relieves external pressure, there’s no need for a stent.

Different Surgical Approaches: ENT vs. Neurosurgical

Bassam: Some doctors enter from the cheek to behind the ear, some from the neck area, some from the mouth. What about your technique?

Dr. Aghayev:

Eagle Syndrome has stayed in the realm of ENT and head and neck surgeons. Unfortunately, they’ve been focused only on the styloid process—not on the jugular vein, carotid artery, or nerves in the vicinity. That led to problems because historically, treatments focused solely on removing the styloid process.

It doesn’t matter what technique or approach you use. What matters is what you actually do during surgery. To have an adequate solution, you must eliminate the root cause. You should remove the part of C1 causing the main compression. ENT surgeons, because of their training, are not trained to do so.

When I do surgery for Eagle Syndrome—which should be called Atlantostyloidal Compression Syndrome—my primary focus is C1. I also resect the styloid process, but the primary focus is removing C1 as the main source of compression. Even after resecting both, there might be residual compression from nearby muscles. In those cases, I find and remove pieces of muscles that are pushing the jugular vein from behind to achieve full decompression.

Symptoms: When Is Surgery Needed?

Bassam: When you see a patient, how do you decide they need surgery? Are there specific symptoms to focus on?

Dr. Aghayev:

People may have various symptoms. Some patients—a minority—come with symptoms related to the styloid process only: pain in their throat or neck when swallowing or even without swallowing, difficulty swallowing, pain in the upper neck area behind the jaw that may shoot into the jaw, teeth, or face. These are the patients classically described by Dr. Eagle.

Another group is different. They come with jugular vein compression. These are the real issues because they may not have any symptoms related to an elongated styloid process—no swallowing issues, no pain in this area, no facial pain. They may not even have a long styloid process.

When it comes to jugular vein compression, the length of the styloid process doesn’t matter. Only the distance between the styloid process and C1 matters. The styloid might be normal, but the space between it and C1 might be narrowed.

Symptoms of Jugular Vein Compression

Dr. Aghayev:

Patients with jugular vein compression have distinct symptoms. These include headaches—particularly position-related headaches that worsen when lying down. When the jugular vein is compressed, blood flow is obstructed. When standing or sitting, gravity helps pull blood down, but when lying flat, there’s no aid from gravity, and blood accumulates in the brain. This leads to increased intracranial pressure (elevated pressure within the skull) and symptoms resurface.

Headaches are usually associated with feelings of pressure inside the brain—patients typically say “there is a pressure inside my brain.” Sometimes the pressure goes so high they have visual problems. Blurred vision is quite typical for high intracranial pressure.

Most patients have tinnitus (ringing or noises in the ears). This might come from turbulence inside the internal jugular vein—when blood flows through the narrow segment, it circulates and creates vortices that produce acoustic waves perceived by the ear. Or increased intracranial pressure itself may cause tinnitus—it’s a well-known side effect.

Another set of symptoms I call “scholastic symptoms”—inability to perform intellectual functions like mathematics and problem-solving. Patients constantly feel foggy brain; they cannot concentrate on anything. Intellectual functions suffer as a result of chronic intracranial pressure hypertension.

How Is Eagle Syndrome Diagnosed?

Bassam: What is the best scan or way to diagnose Eagle Syndrome and jugular vein compression?

Dr. Aghayev:

The most useful test for Eagle Syndrome and Atlantostyloidal Compression Syndrome is a CT venogram (a CT scan with contrast dye to visualize veins) of the neck. It includes part of the brain but mostly shows the veins of the neck—particularly the upper neck area at the skull base, in the region of C1.

CT venogram shows the vein, any narrowing, the length and configuration of the styloid process, the configuration of C1, and everything happening in between. It’s actually a very nice initial test for suspecting the condition. If you have strong clinical evidence pointing to increased intracranial pressure, that test alone may be sufficient to proceed with treatment.

In disputable cases, you can measure pressure at various points of the venous system. You put a catheter inside the jugular vein and measure pressure below the point of compression, above it, and at various points. If you find a gradient—a difference above and below the narrowing—that’s a sign blood has a hard time passing through. But this test is invasive and not performed at every center. In most cases, CT venogram plus strong clinical suspicion is sufficient.

Dr. Aghayev:

When there’s compression in the jugular vein—particularly if bilateral, meaning both left and right jugular veins are compressed—blood finds an alternative way called collateral circulation. Instead of going into the jugular vein and back to the heart, it goes through the vertebral plexus (a network of veins around the spine) in the C1 area and then through the back of the neck to the heart.

Interestingly, when we do surgery and remove the obstruction, the collateral network disappears. This indicates we’ve resected enough bone and expanded the jugular vein sufficiently. The jugular vein becomes like a straight pipe—blood flows vertically like a waterfall with no reason to use the alternative pathway. In some cases, we see this the next day after surgery on CT venogram—the collateral has vanished.

The Vagus Nerve and Related Symptoms

Bassam: We see groups of people talking about the vagus nerve. Is it part of this disease?

Dr. Aghayev:

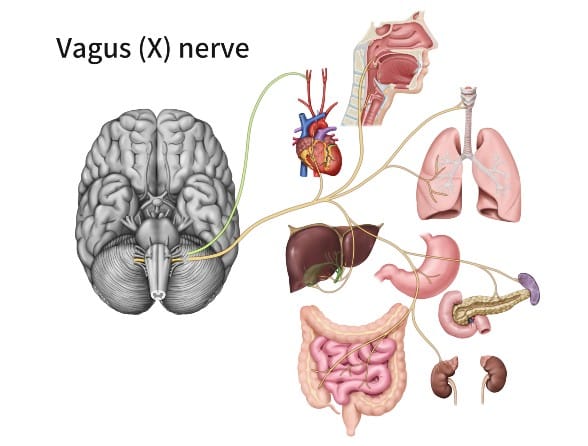

We don’t know because we don’t have very reliable tools—clinically or radiologically—to diagnose vagus nerve (the tenth cranial nerve, which regulates various organ functions) compression or dysfunction. It all comes down to clinical suspicion, but we know that can be misleading. We don’t have good tests to confirm it.

EMG (electromyography, a test measuring muscle electrical activity) of the brachial plexus (nerve network controlling the arm) is much easier to perform than EMG of the vagus nerve—which is essentially unheard of. Right now it’s shaky ground, and some physicians use this term quite broadly.

The same goes for atlantooccipital or atlantoaxial instability. We see an epidemic of so-called craniocervical instabilities where it’s not instability at all. People are being operated on with very vague backgrounds. There are no reliable tools to diagnose these conditions.

Why Do Some Symptoms Disappear After Surgery?

Bassam: Some patients have symptoms like stomach problems before surgery, and after decompression surgery, these symptoms disappear. Why?

Dr. Aghayev:

The only way we can talk about it is in retrospect. If you do adequate decompression surgery and the patient’s symptoms go away, you can retrospectively say it’s very likely these symptoms were caused by the compression. It might not be the vagus nerve—it might be the sympathetic plexus (a network of nerves regulating involuntary body functions), which is in the vicinity of the jugular vein and carotid artery.

I frequently hear symptoms like palpitations or fast heartbeat that come out of nowhere. Patients get evaluated by cardiologists and sometimes treated for tachycardia (rapid heart rate)—but it goes away right after surgery. That might be related to irritation of the sympathetic trunk nearby, not the vagus nerve.

These are symptoms that are somewhat vague and undocumented. We have soft evidence but nothing hard or settled. When I speak to my patients, I mention there’s no hard evidence indicating these problems relate to the compression—but they very likely originate from compression at the C1 and styloid area.

Advice for Doctors and Patients

Bassam: Before we close, what message would you like to leave for patients or doctors listening today?

Dr. Aghayev:

For doctors: I recommend familiarizing themselves with Eagle Syndrome or Atlantostyloidal Compression Syndrome. There are excellent review articles and papers available—even a book called “Eagle Syndrome.” Knowing the disease or syndrome will help them suspect, treat, or at least refer patients to specialists. Knowledge is power, and knowing how to apply that knowledge is perhaps even more powerful.

For patients: There are very nice online sources of information. The truth is that in the vast majority of cases, patients make the diagnosis themselves. They go to doctors who say everything is normal, so they keep searching and ultimately self-diagnose. There are patient groups where you can communicate with others. Surprisingly, many patients with this condition know much more about it than professional doctors do. Most information for patients is on the internet—through social groups or websites.

About Dr. Kamran Aghayev

Dr. Kamran Aghayev, MD, is an internationally recognized neurosurgeon with over 20 years of experience. He’s an Associate Professor of Neurosurgery, practicing in Istanbul, Turkey. With extensive surgical expertise, Dr. Aghayev has established himself as a leading figure in the neurosurgical field, standing at the forefront of the most complex brain and spine procedures.

Watch the Original Interview on YouTube

Learn More About Eagle Syndrome & Jugular Vein Compression:

Eagle Syndrome: A Detailed Review

Jugular Vein Compression: A Detailed Review